2020. 1. 20. 18:45ㆍ카테고리 없음

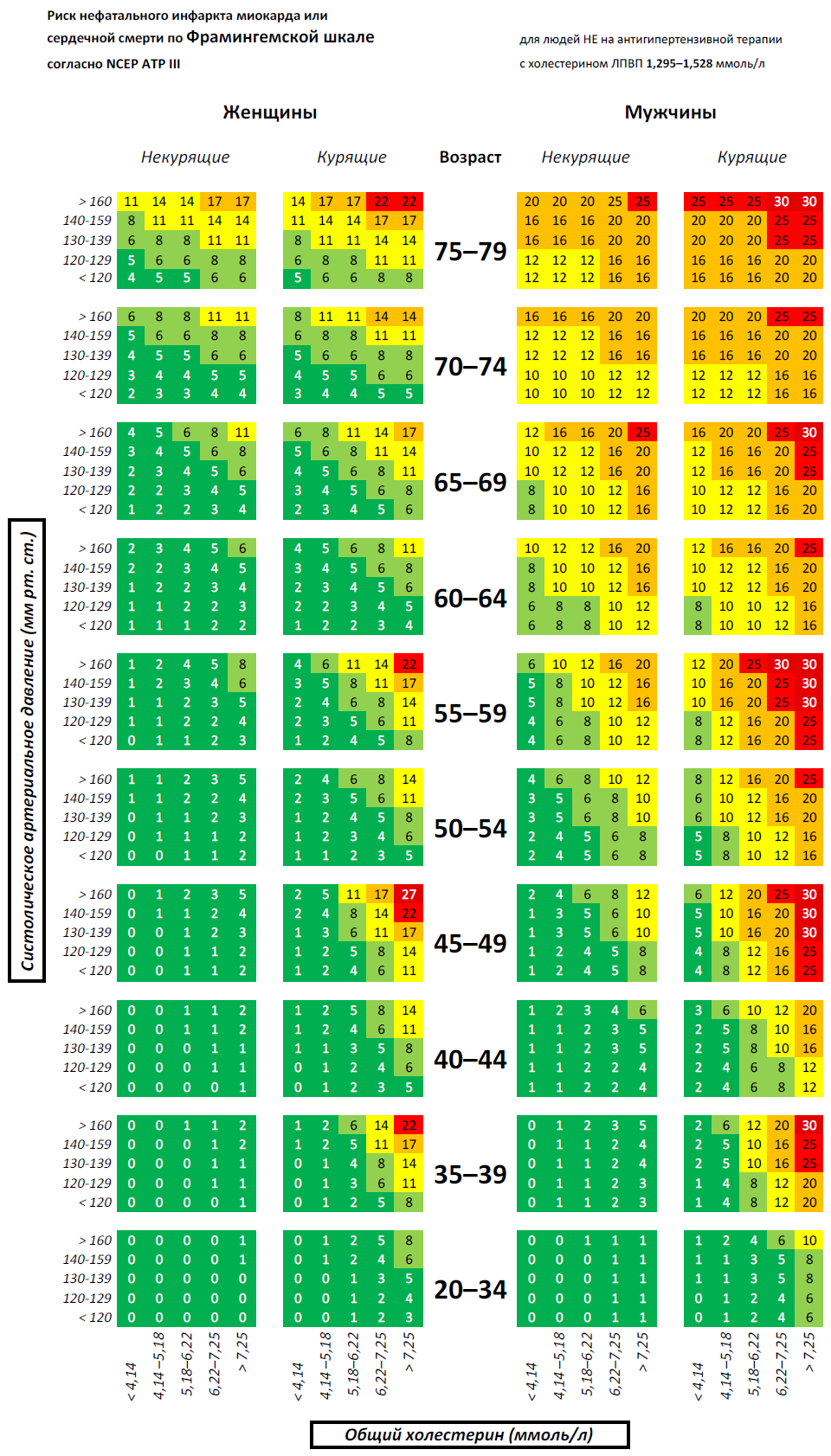

Framingham Risk Score is the estimation of 10-year cvd (cardiovascular disease) risk of a person. It was developed by the Framingham Heart Study to assess the hard coronary heart disease outcome. It is used to estimate the risk of. Adapted from the 'Framingham Study Heart Age Calculator. The Heart Age calculator is meant to be used by individuals 30 to 74 years old who. Microsoft Excel file. Click the Terms tab at the bottom of the app before using the ASCVD Risk Estimator Plus. Indicates a field required to calculate current 10-year ASCVD risk.

PURPOSE: To examine the features of available Framingham‐based risk calculation tools and review their accuracy and feasibility in clinical practice. DATA SOURCES: medline, 1966–April 2003, and the google search engine on the Internet. TOOL AND STUDY SELECTION: We included risk calculation tools that used the Framingham risk equations to generate a global coronary heart disease (CHD) risk. To determine tool accuracy, we reviewed all articles that compared the performance of various Framingham‐based risk tools to that of the continuous Framingham risk equations.

To determine the feasibility of tool use in clinical practice, we reviewed articles on the availability of the risk factor information required for risk calculation, subjective preference for 1 risk calculator over another, or subjective ease of use. DATA EXTRACTION: Two reviewers independently reviewed the results of the literature search, all websites, and abstracted all articles for relevant information.

DATA SYNTHESIS: Multiple CHD risk calculation tools are available, including risk charts and computerized calculators for personal digital assistants, personal computers, and web‐based use. Most are easy to use and available without cost. They require information on age, smoking status, blood pressure, total and HDL cholesterol, and the presence or absence of diabetes. Compared to the full Framingham equations, accuracy for identifying patients at increased risk was generally quite high. Data on the feasibility of tool use was limited. CONCLUSIONS: Several easy‐to‐use tools are available for estimating patients’ CHD risk.

Use of such tools could facilitate better decision making about interventions for primary prevention of CHD, but further research about their actual effect on clinical practice and patient outcomes is required. DISCLOSURE: Drs. Sheridan and Pignone have participated in the development of Heart‐to‐Heart, one of the risk tools evaluated within. They have also received speaking and consulting fees from Bayer, Inc. Has licensed the Heart‐to‐Heart tool.

Clinical practice guidelines recommend that providers and patients base treatment decisions regarding coronary heart disease (CHD) prevention on assessment of underlying global CHD risk. In addition, the American Heart Association has recommended that adults aged 40 and older with no previous history of cardiovascular disease have their global CHD risk calculated every 5 years. To implement these guidelines in clinical practice, providers need an accurate and feasible means of calculating global CHD risk. Previous research has shown that providers do not accurately estimate the risk of CHD events on their own.

Fortunately, multivariate risk prediction equations have been developed to better estimate CHD risk. These equations have been derived from large prospective cohort studies or randomized trials - and estimate a patient's risk of having a CHD event over 5 to 10 years. They provide better estimates of CHD risk than either assessment of single risk factors or simple counting of multiple risk factors and appear to be more cost effective in guiding CHD treatment decisions. Some of the available risk equations, however, have limitations: they include relatively few risk factors; are derived from truncated middle‐aged or male‐only populations; use logistic regression models that require fixed follow‐up periods (e.g., 10 years); treat events occurring at 1 year the same as events occurring at 5 or 10 years; and have been prospectively validated in limited populations. Among the various risk prediction equations, those derived from the Framingham Heart Study are most commonly recommended for use in the United States. These equations calculate the absolute risk of CHD events for patients with no known previous history of CHD, stroke, or peripheral vascular disease (primary prevention). Compared to other risk equations, the Framingham risk equations have favorable characteristics: they were developed in a large prospective cohort of U.S.

METHODS To identify Framingham‐based CHD risk calculation tools and review their accuracy and feasibility in clinical practice, we conducted a search of medline 1966–April 2003 using the MeSH terms coronary heart disease and risk assessment. To identify web‐based tools that are readily available to the clinician, we also performed an Internet search in April 2002 using a popular search engine, google, and the search term “cardiac risk calculator.” Finally, we used our own literature files, and hand‐checking of identified bibliographies and web links to identify other risk tools or articles evaluating risk assessment tools. To identify available CHD risk calculation tools, we included articles and websites that used the Framingham risk equations to generate a global CHD risk, expressed either as the proportion of similar patients who would have a CHD event over a defined time period or as the movement of a patient across a predefined treatment threshold. We excluded articles and websites that used non‐Framingham risk equations, did not specify the equation used for calculation, were designed for secondary prevention, did not clearly define the calculated risk outcome, or calculated risk using nontraditional risk factors such as blood type or measures of psychological stress.

To determine the accuracy of CHD risk tools, we included articles that compared the performance of various Framingham‐based risk tools to that of the continuous Framingham equation in clinical practice. We included articles that tabulated the sensitivity and specificity of the risk tools or provided enough information that these could be calculated.

Because we wanted to focus on tools available for clinical practice, we excluded articles that compared the discriminatory and predictive abilities of continuous Framingham equations including different risk factors or prospectively examined the continuous Framingham equations in large epidemiological study populations. We also excluded articles that examined the accuracy of non‐Framingham‐based risk tools, used a gold standard other than the continuous Framingham model, or that reported only the difference in accuracy among various provider groups. To determine the feasibility of risk tools in clinical practice, we included articles that provided information on the availability of the risk factor information required for risk calculation, subjective preference for one risk calculator over another, or subjective ease of use of the various risk calculators. Two of us independently reviewed the results of the literature and web searches (MP, SS) to determine article and website inclusion. We then abstracted relevant information from included articles and websites into tables for analysis (CM, MP, SS). Disagreements were resolved by discussion among team members. We categorized the risk tools into 2 main groups: 1) risk charts (usually printed); and 2) electronic calculators, including computer programs for personal digital assistants (handheld PDAs), spreadsheet programs designed to run on personal computers, and web‐based risk calculators.

We then reviewed each tool to determine the required input and to characterize its output. For studies reporting on the accuracy and feasibility of various risk calculators, we abstracted information that we felt would impact the quality of the accuracy estimates reported and their applicability to clinical practice. Specifically, we abstracted information on the identity of the risk scorer, whether they were blinded to the gold standard risk assessment, what patient population was used for risk assessment, whether all necessary patient data were available for the risk calculation, and what reference cutpoint was used to distinguish high versus low CHD risk. We made no attempt to combine these factors into an overall quality score. Literature Search Our medline search identified 1,306 articles on risk assessment for coronary heart disease and our final Internet search, conducted on April 28, 2002, identified 3,690 websites.

After review of abstracts and potentially relevant articles, we included 8 articles describing Framingham‐based risk calculation tools and 7 articles providing information on the accuracy and feasibility of the tools. Two independent reviewers additionally reviewed the 100 websites rated most relevant to our search by the google search engine, including 10 sites described in this report. We did not include websites with required member log‐in ( N = 2), nonfunctional links ( N = 3), no CHD risk calculator ( N = 28), non‐Framingham‐based calculators ( N = 7), calculators including nontraditional risk factors ( N = 2), calculators with unspecified risk equations ( N = 5), or calculators with undefined outcomes ( N = 3).

Forty of the 100 sites were repeat references. Tool Characteristics provides a representative, but not exhaustive, sample of available tools. Tools have a variety of formats including risk charts (simple tables or wall charts) and electronic calculators, which are available as stand‐alone or web‐based applications for personal computers, or as stand‐alone applications for personal digital assistants. All tools require information on age, gender, total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking status for risk calculation; most also include diabetes, assessed as a yes/no answer, and high‐density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol. Some tools using older versions of the Framingham equations also prompt input on the presence of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on electrocardiogram, although lack of this information does not preclude risk calculation.

All tools require clinical input of core data including age, gender, SBP, total cholesterol, and smoking status. Additional input listed in column. † Angina includes both stable and unstable angina; MI includes both nonfatal and fatal myocardial infarction. ‡ Birmingham Heartlands calculator makes 3 separate calculations: CHD (MI, Sudden Death, Angina), Stroke/TIA, CVD (MI, Sudden Death, Angina, Stoke/TIA, CHF, PVD). All web addresses active at time of search: April 28, 2002. The output of the risk tools we reviewed is diverse. CHD events are defined alternately as a composite of myocardial infarction (nonfatal or fatal) and sudden death or as new‐onset stable angina, unstable angina (called “coronary insufficiency” in the Framingham study), myocardial infarction, and sudden death.

Some tools (e.g., Sheffield tables, Joint British charts, and Joint European charts) estimate the risk of CHD events alone, while others (e.g., New Zealand tables) give risks for CHD events and for stroke. One tool (Birmingham Heartlands Calculator) also included peripheral vascular disease as an outcome. The presentation of CHD risk (see ) is generally in numeric or graphic terms, with few tools including written explanation of the results. Some tools (e.g., New Zealand tables) give a point estimate of risk, whereas others provide a range of risks or simply state whether a predefined treatment threshold to initiate therapy had been exceeded (e.g., Sheffield tables).

Most tools provide either a comparison to the risk of an individual of the same age or gender who has no risk factors or to an individual with “average” risk factors. Many also provide a qualitative description, such as high or low risk. A minority provide treatment advice or links to evidence‐based treatment guidelines.

Several different risk charts are available in print form or from the Internet. The charts (or tables) generally fall into 2 types: 1 type assigns points to various levels of each risk factor and then assigns a specific risk for the total score obtained after summing the individual scores for each risk factor (e.g., Categorical Framingham tables). The second type arrays information in various combinations of columns and rows either to allow a specific risk to be read from the chart (e.g., New Zealand tables) or to reach a treatment decision given a predefined threshold for treatment (e.g., Sheffield tables). The main advantage of tables and charts is that they do not require a computer for use. They can be downloaded, printed, or photocopied and used in any setting. The main downsides are that they may be difficult or time consuming to use at first and that they are not as accurate or precise as some of the spreadsheet or web‐based calculators described below. Tools for Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs).

Currently, few risk tools are available for handheld computers or PDAs (e.g., Stat Cardiac Risk, the National Cholesterol Education Program Palm Calculator, FramPlus, and Heart‐to‐Heart). Based on the updated Framingham risk equations, these programs use categorical classification of risk factors to estimate the 10‐year risk of CHD. Because they use ranges, they are slightly less precise than some of the spreadsheet calculators that use exact values.

On the positive side, they are portable and very easy and fast to use and can be shared with other PDA users by simply “beaming” the program via the infrared port. Spreadsheet Calculators for Personal Computers. Spreadsheet‐based calculators make the Framingham equations available in a computer program such as Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA). They require that the spreadsheet program be installed on each computer that is to be used for calculating risk. One commercial product, the BMJ CardioRisk Manager, adds the capability of producing more sophisticated reports (including a letter to send results to the patient) and can archive results. It also includes a “slider bar” to allow patients and providers to see the projected effect of treatment on CHD outcomes. The expected effect of treatment is demonstrated by recalculating risk using posttreatment risk factor levels rather than by applying the best evidence about expected risk reduction to baseline calculated risk.

This may be misleading because changes in risk levels with treatment do not produce the same degree of risk reduction as would be predicted from observational studies. Another calculator, the Birmingham Heartlands Calculator, does estimate the effect of treatment, by applying evidence about expected risk reduction. Web‐based Calculators. Several web‐based risk calculators are available.

Framingham Risk Score Sheet

They require that the user have Internet access, but no local software is needed other than a web browser. They can only be used effectively in practice settings that have continuous access to the Internet; establishing a dial‐up connection each time the program is used is impractical. Web‐based calculators generally use the full Framingham equation. Results can be printed from the browser to be placed in the medical record. Additionally, a few tools (the risk calculator from the University of Edinburgh and the Heart‐to‐ Heart tool offer the option to print individualized evidence‐based treatment advice for patients.

Framingham Risk Score Calculator Download

How does this Framingham risk score calculator work? This is a health tool designed to estimate heart disease risk in individuals in a period of 10-years, especially that of coronary heart disease, based on a series of factors identified as cardiovascular risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. It comprises of age, gender and whether the person scored is a smoker or not or under treatment for hypertension; plus three clinical determinations important in assessing cardiovascular function risks: total cholesterol, HDL cholesterol and systolic blood pressure. The criteria considered in this Framingham risk score calculator is detailed below: ■ Gender - Male/Female, this factor is taken in consideration as the points in the following criteria are segmented by gender. ■ Age – this health calculator permits ages starting from 20 to ensure most individual cases of importance are covered, not only elderly people in which, of course, the heart disease risk is proportional to age. ■ Total cholesterol (mg/dL) – a lower TC than 200 mg/dL is considered low risk while 200 to 239 mg/dL is borderline high and everything above 240 mg/dL is high risk.

Framingham Risk Assessment

■ HDL cholesterol (mg/dL) – contrary to the general belief, not all cholesterol is bad cholesterol. HDL is considered the good one as it consists of high density lipoproteins that don’t stick to the arteries forming plaque and leading to atherosclerosis like LDL. Plus, HDL is also able to remove part of LDL, the bad cholesterol away from the arteries and is said to protect against heart attack and stroke when in levels higher than 60 mg/dL. Everything under 40mg/dL HDL is considered high risk for cardiovascular disease. ■ Under hypertension treatment - Yes/No – people with high blood pressure are at risk of coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis) and hypertension treatment can help lower the risk.

■ Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) - This is the first number in the blood pressure reading with the normal range between 90 and 120 mmHg and corresponds to the force with which the contraction of the heart pushes blood in circulation. ■ Smoker - Yes/No – smoking increases heart disease risk by damaging the arterial lining, leading to atheromas which are buildups narrowing the arteries, leading on the long term to very high risk of angina, heart attack or stroke.